(photos, interactive graphics)

CLEVELAND, Ohio -- When Jason Lucas moved to Cleveland from Portland, Oregon, four years ago, he rented an apartment within walking distance of his office on East Ninth Street.

But he quickly started searching for something to buy. And he was shocked by the lack of for-sale housing in the center city.

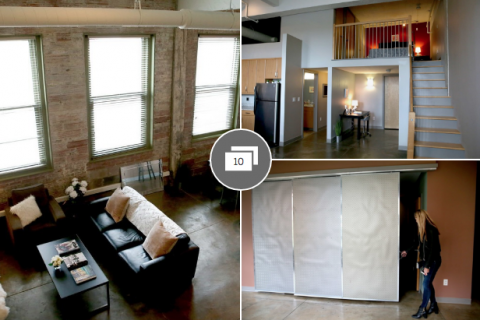

"I love condos. I want to live vertically," said Lucas, a 39-year-old national sales director for AmTrust Financial Services, Inc., a New York insurer with a large office downtown. "I want to live as high up as I can. I want to be far away from yards and garages and window cleaning."

Yet in August 2014, Lucas bought a three-bedroom Tudor in Cleveland Heights. With a yard. A garage. And plenty of windows to clean. He felt like he was throwing away his money on rent. He'd canvassed the condo market, he said, and came up empty-handed.

Urban condo living exists in Cleveland, but the supply is small. The Downtown Cleveland Alliance, a nonprofit group, says there are just shy of 900 condominiums in and near the central business district. There are more than 6,700 apartments. As developers bring hundreds of units of rental housing online each year, vertical, owner-occupied construction sits on the sidelines.

There's not one simple cause for Cleveland's anemic condo market.

Some developers blame skittish lenders and onerous condominium laws for holding them back. Others don't believe there are enough buyers -- with the cash, credit or both -- in Northeast Ohio to go around.

Bankers dispute the assertion that they've blackballed any type of housing. But they acknowledge that condos can be a tough sell thanks to their complex legal underpinnings and the beating the condo market took during the housing bust a decade ago.

"Somebody's got to come out of the gate," said Ted Theophylactos, a Realtor who deals heavily in new construction -- single-family homes and three- and four-level townhouses, mainly -- on Cleveland's near-West Side.

He frequently hears requests, particularly from buyers whose children have grown up and moved out, for single-story living in the city.

"They want one floor," said Theophylactos, who works out of the Howard Hanna office in Ohio City. "They want luxury. They want to own. And we don't have the product."

Lucas, with a 2-year-old son at home, is far from an empty nester. But he has similar desires. He wants a simpler lifestyle, within walking distance of restaurants, entertainment and professional sports venues. If the right condo came along, he'd sell his house in a second.

"There's not a week that goes by that I don't look and wait to hear about some project," he said. "I love my home to death, but it's not where I want to live."

Many conversations, but little construction

In October, developers broke ground for a 26-unit condo building in Little Italy.

That project isn't downtown, of course. But it's a rare addition to the condo market in Northeast Ohio, where the last notable projects emerged from the ground before the financial crisis of 2007 to 2009.

Buyers have reserved or signed contracts on just over 40 percent of the units in the building, called Quattro, at asking prices between $542,500 and $661,500.

As a developer, "if you're going to work in the denser parts of the city, there are two options: Apartment or condo," said Russell Lamb, a principal with Quattro developer Bluewater Capital Partners. "And there's a demographic that's not being served by apartments."

Market research for the Quattro project pinpointed demand for condos in two brackets: Consumers ages 35 to 44 and people 55 and older. That study estimated that there are enough potential buyers to snap up 66 condos each year in downtown Cleveland and University Circle.

The challenge, Lamb said, is making the math work. Land prices are rising. Construction materials and labor aren't getting cheaper. In the apartment market, developers can make units smaller to decrease rents without cutting into their profits. But many condo buyers, particularly those who are downsizing from suburban homes, want ample space and storage.

"I'd like to see the condo market at $300 per square foot," Lamb said, noting that units at Quattro are falling short of that, at an average of $255 to $260 per square foot. "I think you could see more supply if you can be assured that you can sell at a higher price point."

Costs helped derail the Lincoln, a mid-rise condo project in Tremont that got shelved in the summer after nearly two years of planning. In October, another development group bought the land, on Scranton Road, for a mixed-use project. The housing will be rental, not for sale.

At Battery Park on Cleveland's West Side, Vintage Development Group is building more townhouses. The master plan for the neighborhood, on the site of a former Eveready Battery Co. plant, includes condos. But Vintage has struggled to secure funding, since condo buildings must be constructed all at once -- not in phases -- and can carry hefty pre-sale requirements.

Aaron Terrazas, a senior economist with Zillow, said Cleveland isn't unique in its lackluster condo market. After a dramatic boom and bust in the early 2000s, condos resurged in big cities including Boston, Miami and New York.

But in smaller metropolitan areas areas, condos have been slow to come back. The recovery has been weaker, inconsistent -- and incredibly local. Condo sales and construction are more robust in Columbus, for example, where population gains and job growth are driving development.

There are signs that the Cleveland-area condo market might be picking up. For years, condo values weren't keeping pace with the appreciation of single-family homes. That changed in August or September of 2016, Terrazas said, when condo prices started rising at a faster clip.

Data from Redfin, another real estate company, indicates that the Cleveland-area condo market might be tighter than the metropolitan housing market as a whole.

In September, there was a three-month supply of condos being advertised, compared with a 3.7-month supply of all types of for-sale housing. That means it would take three months to sell off all of the available condos, at the current sales pace. Economists often describe a six-month supply of housing as "normal" or balanced, where neither buyers nor sellers have the upper hand.

Conversions far and few between

If new construction is tough, then building conversions -- from apartments to condos -- seem like the next logical step. The Downtown Cleveland Alliance has been talking to landlords about the possibility of turning rental buildings into for-sale housing. But with occupancy at 95 percent and rents inching up, building owners aren't necessarily inclined to take that leap.

"We're just not there yet," said Fred Geis, an owner in the Avenue District tower on East 12th Street, which started its life as condos, failed during the recession and now operates as a high-end apartment building. "We've had many, many, many tenants here look to buy the condos. But it's incredibly difficult to have a mixed condo-apartment development. ... You almost need to be all condos or all apartments."

Condo association laws are part of the challenge of transitioning a building, since there can be a power struggle between a handful of condo owners and a developer who still controls most of the units. But lending -- for buyers, not builders -- is another big impediment.

Rather than holding mortgages on their books, many banks sell loans to Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, two federal government-sponsored entities established to boost access to funds, stability and affordability in the housing market. But many condo buildings and projects in the Cleveland area are considered "non-warrantable," meaning they don't meet Fannie and Freddie requirements for buying the debt.

For example, a condo building isn't warrantable if one entity, including the developer, owns more than 10 percent of the units. It's not warrantable if commercial space accounts for more than a quarter of the building. And it's not warrantable if there's a high share of renters in the building, or if many owners are behind on their association dues or facing foreclosure.

"I think it would be very hard for a downtown condo building to be warrantable," said Mary Ann Stropkay, chief revenue officer at First Federal of Lakewood.

That can put buyers in the position of taking on a riskier loan -- an adjustable-rate mortgage where the bank has more upside, for example. Or, on occasion, avoiding the financing issue by paying in cash, said Kristin Rogers, a Realtor with Howard Hanna who specializes in downtown condo sales.

Rogers is marketing units at the American Book Bindery Condominiums, a recent condo conversion of the Prospect Place Apartments in downtown's Gateway District. A one-bedroom condo there sold in May for $178,900 and a second just changed hands for $160,000. Three more, topping out around $250,000, are listed for sale.

But though they've legally been turned into condos, the remaining homes in the 25-unit building are occupied by renters under pre-existing leases.

"There's currently limited inventory," Rogers wrote in a recent email, "and many people are seriously looking to purchase downtown ... everyone from millennials to empty nesters."

Tax credits muddy the waters

Historic tax credits are another hurdle for condo conversions.

Over the last decade, most of the development downtown has drawn on federal and state tax credits for preservation. Those credits require the owner to hang onto the building for five years, creating a barrier to selling off units. Throw in the complications of a condo conversion, and the switch isn't likely to happen until seven years after an apartment building opens its doors.

At the Schofield Building on East Ninth Street, tenants making significant investments in their apartments have signed long-term leases, for a few years instead of one. That's becoming more common at high-end apartment projects in Cleveland, from The 9 downtown to the One University Circle tower near the Cleveland Clinic and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

The Schofield opened in March 2016 and is essentially full, with tenants paying $1,400 to $6,000-plus a month. The building won't be eligible for a conversion until 2021.

Leasing consultant Marcie Gilmore, who markets the property, said the topic of turning the apartments into condos has come up. But it's too tough to predict what the landscape, both rental and for-sale, will look like in a few years. "If the market were really there for ownership, there would be developers all over it," she said.

Give it time, advised Bob Katitus, a senior vice president and regional market executive with Civista Bank in Mayfield Heights. He pointed to reports that place downtown's residential population at more than 15,000. Some of those renters eventually will want to own real estate. And not all of them will want to buy a house elsewhere in the city, or in Lakewood or Cleveland Heights.

"I think there will be a condominium conversion boom at some point," he said, adding that Civista is willing to look at condos but shares other lenders' concerns about warrantability and legalities. "I hate to use the word boom, but I see that on the horizon."